Catholic quotations from the Church Doctors, Church Fathers and all the great Catholic minds.

Thursday, April 11, 2013

QUOTATION: Faith and Reason

Now there is an additional reason why, of these two, he who is religious will believe more and reason less than the irreligious; that is, if a man's acting upon a message is the measure of his believing it, as the common sense of the world will determine. For in any matter so momentous and practical as the welfare of the soul, a wise man will not wait for the fullest evidence before he acts; and will show his caution, not in remaining uninfluenced by the existing report of a divine message, but by obeying it though it might be more clearly attested. If it is but fairly probable that rejection of the Gospel will involve his eternal ruin, it is safest and wisest to act as if it were certain. On the other hand, when a man does not make the truth of Christianity a practical concern, but a mere matter of philosophical or historical research, he will feel himself at leisure (and reasonably on his own grounds) to find fault with the evidence. When we inquire into a point of history, or investigate an opinion of science, we do demand decisive evidence; we consider it allowable to wait till we obtain it, to remain undecided; in a word, to be sceptical. If religion be not a practical matter, it is right and philosophical in us to be sceptics. Assuredly higher and fuller evidence of its truth might be given us; and, after all, there are a number of deep questions concerning the laws of nature, the constitution of the human mind, and the like, which must be solved before we can feel perfectly satisfied. And those whose hearts are not "tender," [2 Kings xxii. 19.] as Scripture expresses it,—that is, who have not a vivid perception of the Divine Voice within them, and of the necessity of His existence from whom it issues,—do not feel Christianity as a practical matter, and let it pass accordingly. They are accustomed to say that death will soon come upon them, and solve the great secret for them without their trouble,—that is, they wait for sight: not understanding, or being able to be made to comprehend, that their solving this great problem without sight is the very end and business of their mortal life: according to St. Paul's decision, that faith is "the substance," or the realizing, "of things hoped for," "the evidence," or the making trial of, the acting on, the belief of "things not seen." [Heb. xi. 1.] What the Apostle says of Abraham is a description of all true faith; it goes out not knowing whither it goes. It does not crave or bargain to see the end of the journey; it does not argue with St. Thomas, in the days of his ignorance, "we know not whither, and how can we know the way?" it is persuaded that it has quite enough light to walk by, far more than sinful man has a right to expect, if it sees one step in advance; and it leaves all knowledge of the country over which it is journeying, to Him who calls it on.

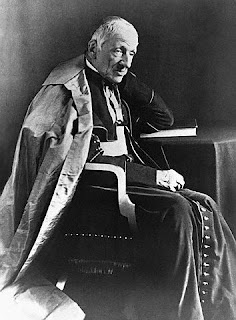

--Cardinal John Henry Newman, "Faith Without Sight", Parochial and Plain Sermons.

Need similar quotes? Try these keywords:

Faith,

John Henry Newman,

Quotations,

Reason